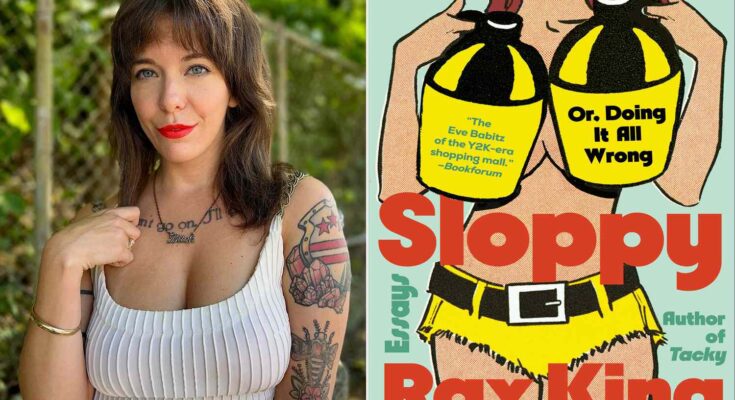

In an exclusive excerpt from her new book ‘Sloppy,’ author Rax King reflects on her time as an erotic dancer and whether going back to school was the right call.

As I lurched tentatively back onto my feet that summer, I didn’t feel any better than I had in the last few dire months before dropping out of college. Not that I expected all my problems to be solved by any job, even one where I got to wear fishnets to work every day. But stripping was a particularly tough job to do well in the midst of a months-long, objectless depression that made even showering feel like an impossible task.

My coworkers must have noticed how much time I spent sniffling in the dressing room. Frankly there was always someone sniffling in there, but those women cried briefly and for a reason, while I cried, more typically, at length and at random. But similar rules apply in the strip club dressing room as in a men’s locker room: Keep your eyes to yourself, and if anything untoward seems to be happening, it’s not your business. The only coworker who ever addressed my behavior was even newer to the job than I was — she must not have known the etiquette yet. Her weird choice of nom de guerre was Ann, an unadorned name that never sounded right when the DJ announced one of her stage sets. (Imagine it now, a deep-voiced man using his best put-your-hands-together voice to say “and now welcome to the stage: ANN!”)

“Are you okay? No, I mean,” she corrected herself, “you’re not okay. I can see that.”

Her question asked and answered, I looked up at her with wet eyes, unsure of where this conversation could go.

“Do you want to talk about it?”

“There’s nothing to talk about,” I mumbled. She nodded, probably assuming I meant things in my life were so f—ed that I didn’t even know where to begin, as opposed to what I did mean, which was that I was just as curious as she was about why I was crying.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(499x0:501x2):format(webp)/king9780593688458aup1-60738e6a1cb14ca7aea1cd074420546f.jpg)

We chatted a bit, and she learned that I’d just dropped out of school, while I learned that she was starting her freshman year in the fall. That made her the only stripper in the place who was even younger than I was, which made me emotionally itchy — I’d come to take pride in being the baby of the dressing room. On top of that, Ann was blessed with golden-tan sorority girl prettiness, which I noted with dim jealousy somewhere in the part of my brain that wasn’t focused on crying. I was still prone to jealousy of the ways other strippers were attractive that I was not. I hadn’t yet slipped into that easygoing, temperate stripper’s way of relating to my coworkers and their beauty. Ann, though this was only her second day at the club, had that mode down pat.

She showed me a picture of her boyfriend, a much older man about whom the kindest thing I could think to say was that at least the shadow from his bucket hat hid most of his rodent face.

A Shady Invitation and a New Perspective

“Beautiful,” I said. It was the wrong word, but she’d caught me off guard with how profoundly hideous he was. Then she asked me whether I wanted to come out with them after work to a place where I could make some real money, and the equation solved itself in my head. One middle-aged scumbag in a bucket hat + one young and outgoing stripper girlfriend + one invitation to the lowest earner in the dressing room to “make some real money” = pimp. I declined the invitation, and she thumbed away my running mascara before leaving the dressing room for her stage set, telling me to let her know if I changed my mind.

The next day, Ann was gone. Edina told me she’d run out on the last hour of her shift with a customer. She’d called the club in the morning to say she was in Detroit and she quit. The biggest surprise was that she’d called.

That same day, Liv urged me to harpoon a whale — to make one of the richer and more generous men into my personal regular customer. “A whale gives you job security,” she said. “Otherwise, every day is a struggle. Not to imply that, like, your life is a struggle …”

“No, no,” I said. “Imply away.”

Liv had noticed my reticence with the customers, my general desire to get away from them as quickly as possible. I was the only dancer in the club who preferred grinding onstage for singles to slowly draining a guy’s wallet at his table. The explanation was simple. Onstage, I didn’t have to talk to them.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/stripper82-072825-98d43c2bff7649fcaa2a12d422da726b.jpg)

I could blame the customers for my standoffish attitude, and you’d probably believe me, but I must be fair. This was 100 percent free-range zero-antibiotics-added Rax’s problem. As a girl, I’d been so shy with men and boys that I could not force myself to speak to any who weren’t my father. I eventually developed an erotic interest in men, which helped. Flirting, asking a man about himself, these behaviors came to feel natural—with men I wanted to sleep with. But traces of my girlish fear remained, so that I struggled to chat up any men I didn’t find attractive.

In a strip club, that ruled out most of the customers. I fished tadpoles over and over again, sexy young men who were too broke for the club, while tips from my coworkers’ whales paid my bills. In the delicate strip club ecosystem, I was a parasite. Mine wasn’t the only ass getting bitten by my behavior.

Luckily, I harpooned a whale.

The Unlikely Path Back to Academia

It was a complete accident, as are most instances of me being good at my job. My stage set had just ended and I was taking my customary lap around the room, holding out the garter on my leg so that the customers who hadn’t come up to the stage to tip me had an opportunity to do so now.

(This is admittedly a pretty strained use of the term “had an opportunity.” What they really had was me, smiling in their faces, refusing to walk away until I’d parted them from at least one dollar.) As I collected my tips, I noticed an elegant man in his fifties at a table with a young one. The older man was animatedly gesturing with a cocktail stirrer, and I caught a snippet of his lightly accented lecturing as I approached.

“… which we can clearly trace back to Alcibiades’ speech about the cleaving of the original human soul in the Symposium!”

“Aristophanes,” I said.

Both men blinked, looking a little dazed.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, reddening. The younger man turned back to his silver-haired friend, clearly hoping, as many customers did, that I would give up on my tip and go away if he was rude enough. But the older man’s eyes hadn’t left my face.

“I did mean Aristophanes,” he said. From his billfold he withdrew a twenty, so new and crisp that it stuck to the others. He tucked it into my garter. “Very good.”

From then on, Dimitri the classics professor came to talk about Plato with me every week. That was all we did, talk Plato, and as long as I stayed sharp and engaged, the twenties kept flowing.

Weirdly enough, those talks with Dimitri helped convince me to take another stab at college. Having him as a customer meant that my income at the Castle was finally reliable, which gave my depression some space to ease up. As the fog lifted, I looked at my former classmates with new anxiety. They were advancing towards a goal that I’d recklessly abandoned; they, and not I, would have degrees in two years. I didn’t even know what I’d do with a degree once I had one, but what I really couldn’t stand was feeling myself get left behind.

Lola’s Farewell and Sasha’s Debut

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(599x0:601x2):format(webp)/Sloppy-by-rax-king84-072825-6bb4671419cc4d5899a4ccd5d3e345a5.jpg)

I reenrolled, and the Castle had a big party for me on my last night, which also happened to be my birthday. Edina baked a cake for me which read: Happy 21st to our Baby, Lola! We Will Miss You! That had been my name at the club — Lola.

I would miss the Castle, and I would especially miss being Lola, who took no s— and made great money. Now that I was leaving, it felt like Lola, and not I, had learned the secrets of maintaining a sexy hairstyle in the humidity. She could walk gracefully in heels, she could set firm boundaries with men and she’d even been generous enough to pay down that wastrel Rax’s considerable credit card debt. Why was I giving up a persona of such power? To go back to sleepy Annapolis and read a thousand long-ass books about what it meant to be alive?

Liv was glad for me that I was going back to school, because it was what I said I wanted, but she had to admit she agreed with me on that last front. “School and books can all wait. These are the years for making your money,” she said, helping me stuff the night’s cash into my gym bag.

I’d always been told to be patient, study hard, work hard, be responsible, and eventually the money would come — a reward for making all the right choices, the lollipop after the root canal. Now here was Liv, pointing out that the time for my money was now. That there was no need to be patient, that here was something I could grab whenever I wanted and indeed I’d be stupid not to. I saw what she meant: at 21, I still had plenty of time to rebound from the nightly hurt I was putting on my knees as I crawled and bounced on them, shredding their ligaments, bruising them purple.

Then, too, I had five or six years left of sweetly telling men I was stripping to pay for college, an evergreen moneymaker of a lie.

“All that, too,” Edina agreed, “but come on. You’re a baby. No way you can do books and school right now.”

I needed to hear that. For one thing, it strengthened my resolve to go back — I’ve always had an easier time committing to things that someone else has confidently predicted I can’t do. But also, Edina turned out to be right that I was a baby, and it was helpful to remember the way she lovingly excused me for it. Once the school agreed to take me back, I lost my drive to chase my degree and spent my last two years of college in damage-control mode, forever catching up on work I had no real interest in. And every time I didn’t do my homework because some man wanted to take me to a party that evening, every time I snorted a Percocet instead of going to a lecture, I heard Edina’s warm, patronizing voice: Come on! You’re a baby!

The Siren Call of the Stage

I graduated college two years later by the skin of my teeth, with a C average and no job opportunities in my future. My résumé was useless, even when I proudly presented my brand-new bachelor’s degree at the very top of it. Employers with blazer jobs in desk-offices weren’t impressed by my history of food service and other customer-facing positions. After months of fruitless job searching, I began to hear the siren call of one particular customer-facing position: legs spread, ass shaking. Money, lots of it, leaking out of my straps and garters.

I didn’t want to go back to the Castle. Anyone there who remembered me from my first stint would remember me primarily as a teary-eyed parasite of other dancers’ money. I wanted to try again somewhere new, where I could be smart and calculating from the start, and no one would have to know that I ever hadn’t been.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/stripper83-072825-2338ed62007b4843a07685782df8a972.jpg)

I went to an unfamiliar club to audition with my trusty old gym bag full of wrinkled costumes. The audition went fine — not 10-dollars-for-two-minutes’-work fine, but fine. I wasn’t green anymore and therefore I didn’t care anymore, which meant my money would be both better and worse. Some men rip you off when they can smell your inexperience, others get off on their generosity with the fresh meat. I’d have to figure out the rhythms of my money from scratch. I would need to harpoon a whole new whale, or else dig up the last one’s carcass from the prepaid cell phone where I’d had his number saved.

When my song was over, I put my clothes back on and met the club’s manager in the dressing room. She was a big harried woman with sleek black hair falling down her back, and she did not seem happy to see me.

“Fine,” she said. “Can you start tonight? What do we call you?”

“Lola, please.”

“Already got a Lola,” she said irritably. Everything she said to me the whole time I worked for her, she said irritably. “Can you be Sasha? We just lost our Sasha.”

“Fine,” I said.

A new name to remember to answer to; a new name for men to react to in some new way. I supposed I would have to be Russian this time. I’d miss Lola, sure, but at the end of the day it made no difference what they called me. The power was what mattered — the power, which my supposedly invaluable degree had failed to confer, to earn a living.